🚀 Inside the Minds of VCs: How UK Funds Evaluate Startups (Part I of IV)

Part I of IV — A Deep Dive into Pre-Investment Decision-Making in Frontier Tech

Welcome to 22nd Century Frontier — your strategic edge in innovation, investment, and entrepreneurship. 🚀

"Audentes Fortuna Iuvat"

~ Latin Proverb

What really drives investment decisions in high-risk, high-reward frontier technologies like blockchain?

Today, we kick off a 4-part premium series uncovering the strategic frameworks used by UK-based venture capitalists when evaluating blockchain startups. This research, conducted in collaboration with four seasoned UK VC funds, is based on 5 months of deep investigation—combining deal data, market insights, and candid one-on-one interviews with fund partners.

This was not desk research.

It was fieldwork—gathered during a time of rapid transformation in blockchain and adjacent frontier technologies. At the heart of this series is a powerful dataset: 517 funding rounds by 220 UK blockchain startups, with 48 of them backed by 33 domestic VCs.

The project was completed some time ago, but has remained confidential for nearly four years due to the sensitive nature of the market intelligence uncovered—until now.

For the first time, we’re lifting the curtain.

What You’ll Discover in This Series:

Part I: Laying the Foundations

Origins & Evolution: A concise history of private equity and venture capital—from a £1k‑industry in 1946 to today’s multi‑billion‑pound market—and why VCs matter for frontier innovation.

Problem Definition: Why VC decision‑making remains shrouded in mystery, and the gap this research fills for entrepreneurs and investors.

Aim & Objectives: Our four guiding questions—from mapping the UK blockchain‑startup ecosystem to contrasting due‑diligence in frontier vs. traditional sectors.

Methodology Unpacked: How we built our three‑stage research framework—data mining 517 deals, semi‑structured interviews with four leading UK funds, and a rigorous literature comparison.

Report Roadmap: A quick tour of this series’ structure and how each part connects to deliver a complete VC playbook.

Part II: Decoding the VC Screening Playbook

Demystify the full VC playbook: From why they back pre‑revenue startups and how they outpace public markets, to the seven screening pillars that narrow hundreds of pitches down to the few they back—complete with data‑driven rankings and candid insights from four UK fund partners.

Part III: Unveiling the Findings & Discussion

Navigate the UK VC Playbook: We’ll chart the UK frontier‑tech ecosystem, uncover the five proprietary deal‑sourcing strategies VCs use, guide you step-by-step through their pre‑investment process and seven core screening pillars, and reveal the unique twists in evaluating blockchain ventures versus traditional startups.

Part IV: Mastering VC’s Art vs. Science

Unveil VC’s Ultimate Playbook: Uncover why VCs place founder & team quality above all else, how they rank and apply seven core screening pillars into a rigorous due‑diligence engine, the extra hurdles they set beyond the pitch deck, the unique curveballs of blockchain diligence, and how their role pivots post‑investment into network stewards rather than traditional board members.

This is the kind of intelligence we created 22nd Century Frontier to deliver: original research, untold insights, and decision-making frameworks you can’t find in public databases or news feeds.

Welcome to the inner circle.

Let’s dive into Part I.

Premium Bonus 🤖

Get practical, YC‑backed advice on starting and scaling your startup—just ask a question to the YC Startup Advisor chatbot.

(Check the end of the article for access.)

Table of Contents

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

1.2 Problem definition

1.3 Aim and objectives

1.4 Methodology

1.5 Research structure

2 Literature Review

2.1 Blockchain - Analysis of the sector

2.1.1 What is blockchain and how does it work?

2.1.2 Industries disrupted by blockchain

2.1.3 The UK's blockchain business landscape

2.2 Private Equity (PE)

2.2.1 Private Equity Fundamentals

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Following its origination in 1946, private equity deals and operations have expanded considerably from a thousand-pound sterling industry to a billion-pound sterling one (Bain and Company, 2021). Private equity has been an area of interest for academic and financial research as a result of its considerable development over the last three decades and its ability to serve as an alternative asset investment class, which has been advocated by much of the financial and independent press. Private equity (PE) and its subset venture capital (VC) emerged in the last decades as the ideal vehicle for channelling private and public money into the financing of innovation. Indeed, both private equity and venture capital funds are temporary equity investors that provide capital, in return for equity (shares), to non-listed firms with strong growth potential (Private Equity Council, 2007).

Venture capitalists (VCs) generally invest in young, high-technology firms with the potential for fast development (Metrick and Yasuda, 2011). The start-up economy has lately flourished in the UK, and early-stage start-ups require capital to fund their development (Financial Times, 2021). VC finance is a fundamental and essential source of funding for high-technology and risky start-ups. As a result, venture capital is seen as an essential piece of the entrepreneurial economy (Mason and Harrison, 2002). In 2019, the investment activity into the UK start-ups and scale-ups ecosystem showed 821 investments which equate to £1.65 billion (British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association, 2020). In recent years one of the most attractive and controversial industries is blockchain (McKinsey & Company, 2018). Blockchain technology is the core of 5 out of 6 of the UK's fastest growing sectors in 2020: Digital security, insurtech, crypto currencies, fintech and challenger banks (Beauhurst, 2021b).

The ability of VC companies to predict new firm performance throughout a multi-stage evaluation process of investment proposals is critical to their success. VCs might well be considered as experts in discovering high-potential start-ups – 'gazelles' (Zacharakis and Shepherd, 2001). As a result of this circumstance, the academic community in the field of entrepreneurship and finance has given greater attention to the VC evaluation process (Kaplan and Str¨omberg, 2004; Gompers et al., 2017). To date, the majority of research on VC decision making and investment criteria has been undertaken mainly in the United States (see Table 2‑1). Little attention has been given to documenting the actual pre-investment process in the UK and VC's investment criteria, especially for VCs who invest into sectors such as blockchain.

1.2 Problem definition

The PE industry is surrounded by a halo of secrecy, and not only the general public but also many entrepreneurs do not fully understand how VC funds works and what makes VCs take the decisions they take. There is limited literature that brings together the decision-making process for VCs to go through when choosing in which companies to invest.

1.3 Aim and objectives

This research aims to contribute to the literature on entrepreneurship by providing a clear set of findings regarding how VCs make decisions.

Thus the objective of this study is to understand and assess the VC pre-investment process and identify the investment criteria thereby narrowing the gap between academia and practice.

In order to address the research objective, the following four sub-questions will be addressed:

1. What does the UK blockchain start-up and VC landscape look like?

2. How does the VCs pre-investment process work?

3. Which pre-investment screening and due diligence criteria do VCs use in the evaluation of start-up ventures and the team?

4. What is the difference in pre-investment screening and due diligence for blockchain start-ups in comparison to investing in traditional start-ups?

1.4 Methodology

To accomplish the above stated objectives, a research framework split into three main parts has been established.

The first part involves secondary data research of publicly available data in order to identify the blockchain startups that have received funding from VCs, then to identify all of the VC firms that have invested into blockchain and finally to create a landscape map of the British VC blockchain investors.

The second part consists of semi-structured interviews with VCs.

The third part comprises an analysis of the results and comparison with the existing literature.

1.5 Research structure

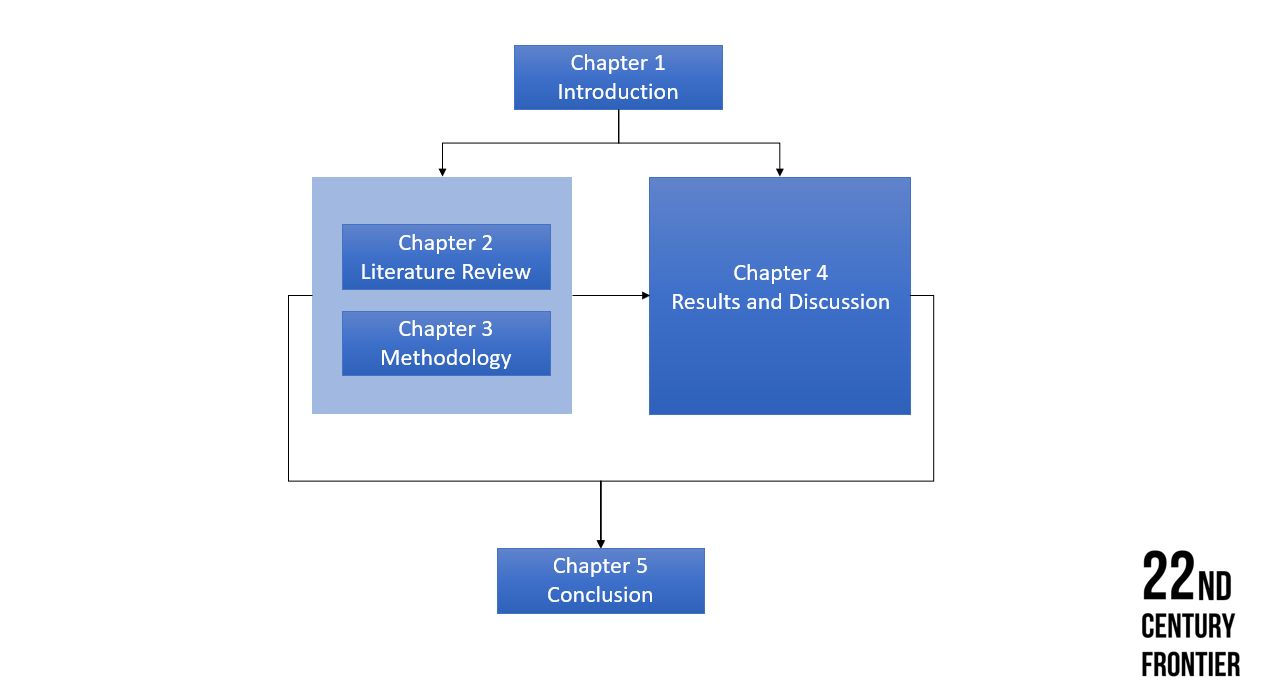

The research is organised into six chapters, see Figure 1‑1.

Chapter 1 defines the background of the topic, the research questions and purpose of the study.

The second chapter consists of a literature review of existing research. This research is designed to deliver an understanding of the blockchain sector. Thereupon, the concept 'private equity' is defined. The PE subset – Venture Capital is explained in detail, followed by explanation of the investment process and the commonly applied pre-investment screening criteria and due diligence process.

In the third chapter, the research method, data collection and interviews are explained.

Chapter 4 analyses the results of the collected data and compares the study to previous literature, in particular how this study supports and differs from the earlier findings.

Finally in Chapter 5, the introduction of the limitations of the study and suggestions for further research are proposed.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Blockchain - Analysis of the sector

The term "Blockchain" was established anonymously in 2008, by someone under the pseudonym 'Satoshi Nakamoto', following the release of his white paper Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System (Nakamoto, 2008). The introduction of blockchain triggered the development of a number of blockchain start-ups applying the technology to disrupt conventional industries such as banking industry services, legal services and healthcare (Beauhurst, 2020).

2.1.1 What is blockchain and how does it work?

According to a definition provided by Nakamoto (2008), a 'block' is an online file that holds a set of transactions. Blocks are linked in a chronological and linear 'chain' of records. Every block has three major data parts: transactions information, a unique 'hash code' used to identify the block, and the hash-code of the preceding block in the chain. Whenever a block is added to the chain, it becomes immutable, which means it cannot be deleted or modified in any manner. Any action to alter the block will result in the creation of a new hash code, which will contradict with the hash in the next block. Without the need of a third party, blockchain enables non-trusted entities to reach an agreement on the blockchain database condition (Nakamoto, 2008). The technology is a digital ledger that allows transactions to be verified and securely recorded without the use of a central authority or middleman (CB Insights, 2021).

2.1.2 Industries disrupted by blockchain

Blockchain can be used to record any-sort of electronic data and contributes to more transparent and efficient supply chains. The technology is gaining traction in a variety of high-growth industries such as financial technology (FinTech), artificial intelligence (AI), security, electronic commerce (E-commerce), and Internet of Things (IoT).

2.1.2.1 Blockchain in banking and financial services

Blockchain-banking provides cost-effective, faster, and secure payment alternative to traditional financial institutions (Deloitte, 2016). Previous study of blockchain in finance have identified that blockchain banking will require banks to produce their own digital-currencies and distributed ledger systems for payment-processing, comparable to Bitcoin (Varma, 2019). Due to the decentralised nature of blockchain, no intermediaries service-fees would be collected. This is especially beneficial for cross-border financial transactions; by using the technology, overseas participants may save money on exchange rates and financial service fees. Blockchain banking is also a more efficient method since payments are executed as soon as they are validated. Furthermore, due to the immutability of blockchain and its sophisticated cryptographic-secured network, transactions are extremely safe (Catalini and Gans, 2020). This secure payment channel provides unrivalled security against hackers, allowing payments to be fully secured.

2.1.2.2 Blockchain in legal services

Processing and storage of sensitive information is a significant portion of the legal services sector.

Contracts

Through 'smart contracts', the legal services sector may benefit from blockchain's capacity to securely store contracts. A smart contract is a blockchain-based digital code that monitors and implements legal agreements automatically (Nash, 2019). Smart contracts can be utilised when the triggering event of a contract can be measured electronically, such as received payments or public-registries update. As a result of the automation, the necessity for attorneys to monitor contracts is reduced.

Conveyancing

According to Nash (2019), blockchain technologies can also help to ease the transfer of property from sellers to purchasers. The conveyancing process involves numerous participants such as buyers, sellers, legal-representatives, and banks, as well as various documentation such as transfer of land-contracts and certificates of title. Dealing with this many papers and parties is typically a time-consuming and complicated procedure. Instead, keeping property details and necessary documentation in a block that all parties can see would decrease-correspondence between participants and data requests, save-time, and maintain confidentiality.

2.1.2.3 Blockchain in healthcare

In the healthcare industry, essential patient information such as individual data records and medical insurance claims are held in separate systems (Ratta et al. 2021). The blockchain architecture provides a readily shareable and secure patient management system. This could be accomplished by storing patient data within a block. Once the patient's agreement has been obtained, these digital-assets can be shared in real time with other medical-institutions and-practitioners.

2.1.3 The UK's blockchain business landscape

Between 2019 and 2020, the industry saw a 1,533 % rise in deal value and a 113 % increase in deal volume (Beauhurst, 2021c). In 2020, £539 million was invested over 32 transactions. Through the coronavirus pandemic, the high-growth economy leant on digital sectors for growth. Fintech, blockchain and digital security companies received record investment, while artificial intelligence deals dropped off (Beahurst, 2021c). There are 221 UK private firms developing blockchain-driven software and blockchain services in 2021. (Beauhurst, 2021d). The great majority (67 %) of these firms are in the seed stage of development, reflecting the sector's youth.

While blockchain has many applications, 41 % of blockchain start-ups are in the Business and Professional Services, mostly in banking and finance, but also in security, analytics, payment processing, insurance, and legal. In comparison, 2 % operate in the Supply Chain industry, 2 % in Leisure and Entertainment, 1 % in Retail, and 1 % in Industrials.

This exemplifies how blockchain technology is increasingly being used to disrupt established business processes.

2.2 Private Equity (PE)

2.2.1 Private Equity Fundamentals

Private equity (PE) refers-to the source of capital, as opposed to public-equity which can be raised on the stock-exchange.

PE is a type of financing that is offered in exchange for an equity-stake in potentially high-growth firms. Transformation in the firms is achieved through collaborating with the firms's management to enhance performance and strategic direction, making complementary investments, and pursuing operational excellence.

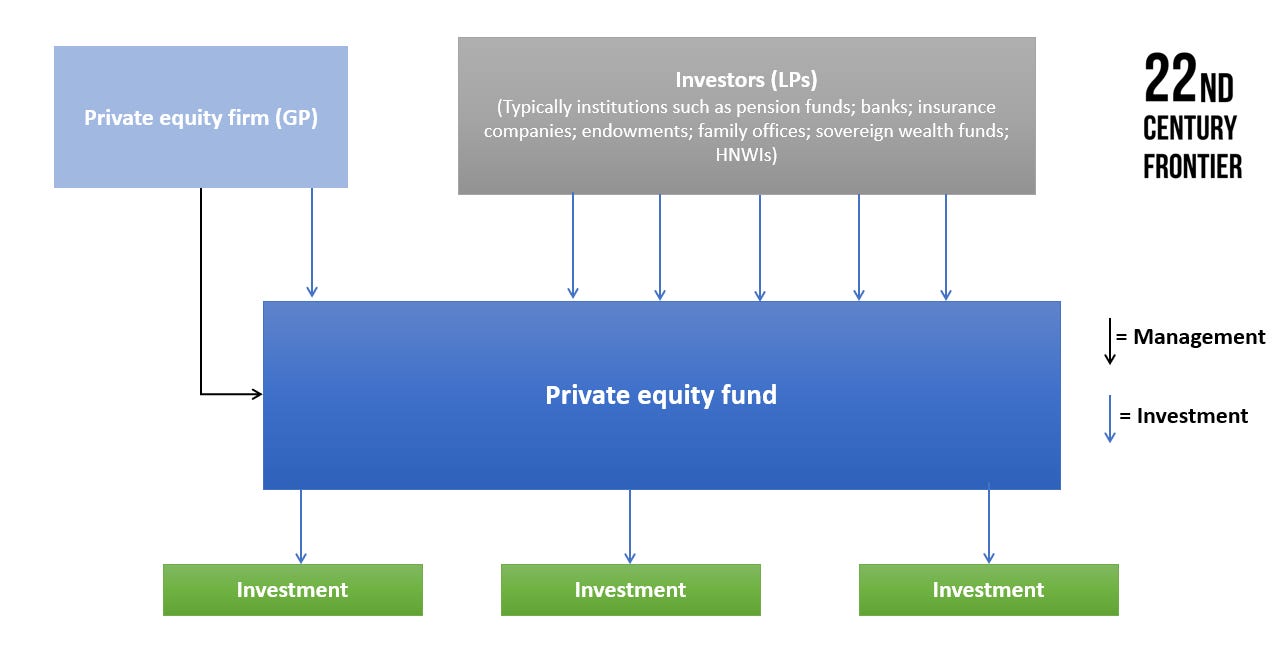

Figure 2‑1 illustrates typical PE process. Instead of selling shares on the stock exchange, PE companies raise capital from third-party investors such as pension-funds, family offices, insurance firms, endowments, and high-net-worth-individuals (HNWIs) (Rosenbaum and Pearl, 2009, p. 163). Investors unite with a fund manager in an investment partnership, with investors serving as Limited Partners (LPs), and the manager serving as General Partner (GP). The fund then invests in often-majority stakes in firms with high-growth potential, with the goal of enhancing the firm's value and performance and selling it for a profit at a future point in time.

This sale will often occur five to seven years after the initial investment, demonstrating long-term ownership over which major operational adjustments and other enhancements may be implemented. This is known as an exit, and it is accomplished by selling an investor's stake in a firm, often through a public-market listing in an initial-public-offering (IPO), selling the company to management (buyout), or to a strategic-buyer (trade-sale).

In contrast to other asset classes, where capital is pulled down all at once, PE commitments are drawn down over time when investments in various firms are undertaken. PE funds are designed to be a long-term investment, where limited partners (LPs) are required to commit their investment for the duration of the fund's life – usually 10 years. The lifespan of a PE fund is generally divided into a five-year investing period followed by a five-year disposal period. PE is illiquid due to the long-term nature of its investment strategy.

According to the British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association – (BVCA) (2012a), in principle private equity comprises a range of investment fund types, including:

Buyout fund: Funds that target mature companies with stable cash flows. They seek to finance the transaction with mix of equity and debt in order to obtain controlling stakes.

Generalist fund: Funds that invest in all stages of PE.

Growth fund: Funds that target mature companies that are entering into new markets and are expanding their operations organically or though merger and acquisition (M&A) activities. They tend to be quite generalist in terms of industry scope.

Mezzanine fund: Funds that use a combination of debt and equity-financing, including equity-based options (such as warrants) and subordinated-debt.

Rescue/Turnaround fund: Funds that invest in firms in financial distress with the goal of returning the firm to profit.

Venture capital funds:

· Seed: Typically, small funds (some tens of millions), investing in very early-stage companies with a product or service under development. In the majority of cases, the company has not begun commercial operations. The investment in this firms range from a hundred thousand to a few hundreds of thousands.

· Early stage/Start-up: Medium-size funds (around 100m) targeting companies that already have a product or service in the market, with growing revenues and traction, but still trying to scale operations and fine tune the business model. The fund would invest from one to a few millions in the round.

· Late stage/Expansion: The funds can have several hundreds of millions to invest in mature companies, with solid products or services and a consolidated business model. These companies might be looking to expand their activities and tackle markets on a global scale. The investment in the rounds could amount to several tens of millions.

In this research, Private Equity will exceptionally refer to Venture Capital, due to the early stage of the blockchain industry and its attractiveness to the private equity industry.

Check the YC Startup Advisor below 🤖👇

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to 22nd Century Frontier® to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.