The Three Numbers That Decide Whether Your Startup Survives Or Dies

CAC, LTV, Payback Time

Most startups do not die because the idea was wrong.

They die because the math was ignored.

Founders spend months debating vision, features, and positioning, then quietly assume the numbers will work themselves out later.

They rarely do.

Under every successful startup is a simple economic engine.

Under every failed one is a version of that engine that never quite closed the loop.

This piece breaks down the three numbers that quietly decide whether your company compounds or collapses:

What it costs to acquire a customer?

What that customer is worth over time ?

How fast your cash comes back?

No hype.

No spreadsheets for show.

Just the mechanics that determine survival.

Sponsor Highlight: EuphoriaTech Group ✨

Where founders, executives, and top creators connect

EuphoriaTech Academy is a community-first membership giving you access to Influencer Syndicate Communities and a Founder & Executive Network.

Collaborate, share insights, and build real opportunities with people actively shaping tech and business.

Key Takeaways

Your early metrics will be wrong, but their direction matters more than precision

You do not need perfect data. You need numbers that get closer to reality over time, not numbers designed to impress.CAC always expands as you scale

The channels that work early are rarely the ones that carry you to scale. Plan for rising acquisition costs, not falling ones.LTV defines how much risk you can afford

High lifetime value buys you time, flexibility, and optionality. Low LTV demands ruthless efficiency from day one.Payback time determines how fast you can grow without outside capital

Short payback creates compounding growth. Long payback forces dependency on funding or patience.Scaling before validating payback is the most common founder mistake

Growth does not fix broken unit economics. It amplifies them.

Table of Contents

Why Most Startup Advice Misses the Point

The Three Numbers That Quietly Decide Everything

Customer Acquisition Cost: The Number Everyone Underestimates

Why CAC Rises, Not Falls, Over Time

Lifetime Value: What Customers Are Actually Worth

Payback Time and the Hidden Cash Flow Trap

What Good Payback Numbers Actually Look Like

The Trap of Believing Your Own Spreadsheet

The Three Phases Where Numbers Mature

A Practical Way to Evaluate an Idea Before You Build

Final Thoughts: Stories vs Businesses

1. Why Most Startup Advice Misses The Point

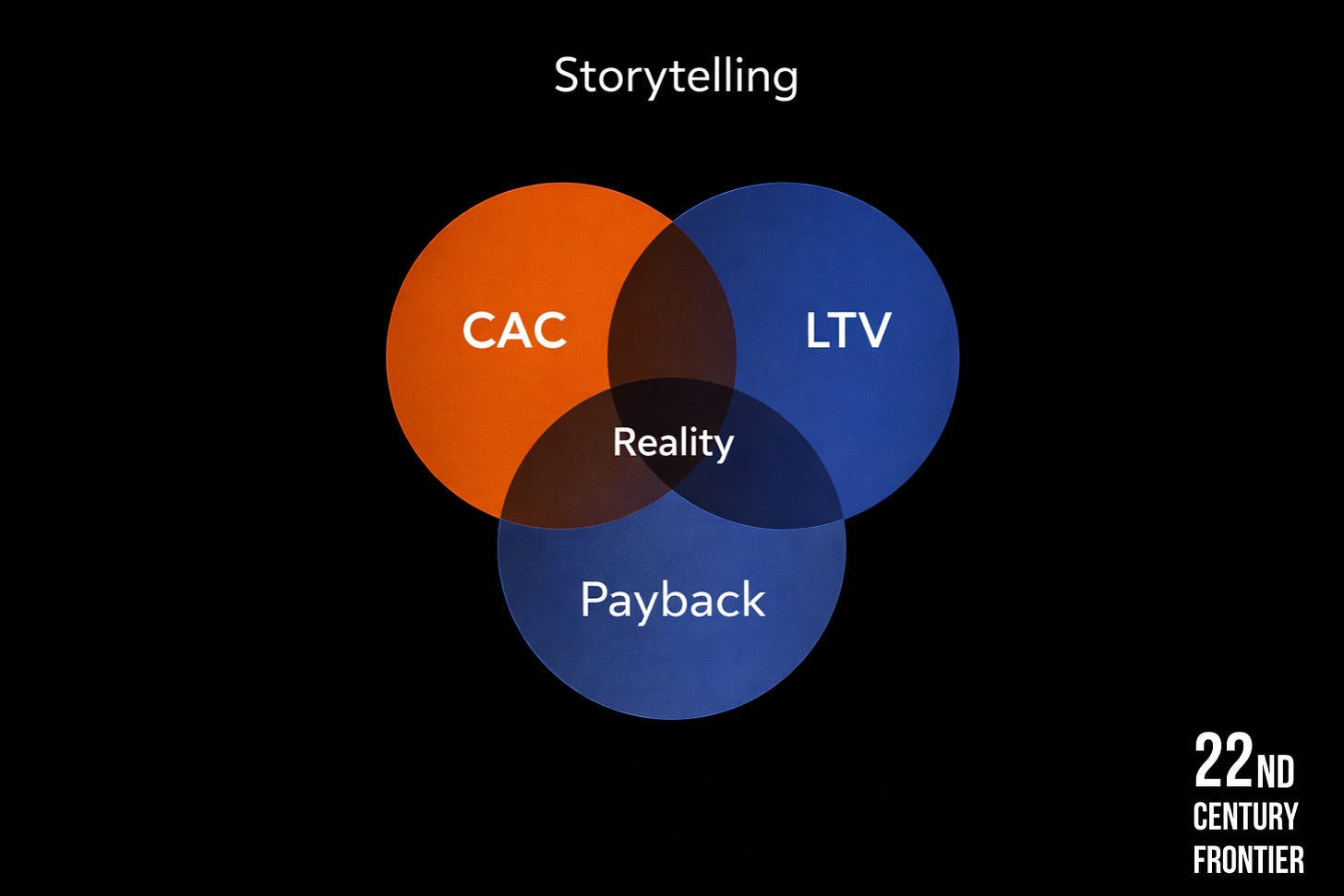

Startup advice tends to orbit around vision, storytelling, culture, and ambition.

Those things matter.

But they only matter after the business survives.

A startup is not validated by press coverage, demo days, or investor interest.

It is validated when money comes in faster than it goes out, repeatedly, without heroics.

After watching dozens of early-stage companies up close, one pattern keeps repeating:

Ideas fail less often than economics.

Founders usually do not die because the product is bad.

They die because customer economics quietly poison the business before anyone notices.

When I evaluate a new business, I ignore almost everything at first and ask three questions:

What does it cost to acquire a customer?

How much does that customer pay over time?

How long does it take to earn back what you spent?

If you cannot answer those three with reasonable confidence, nothing else matters yet.

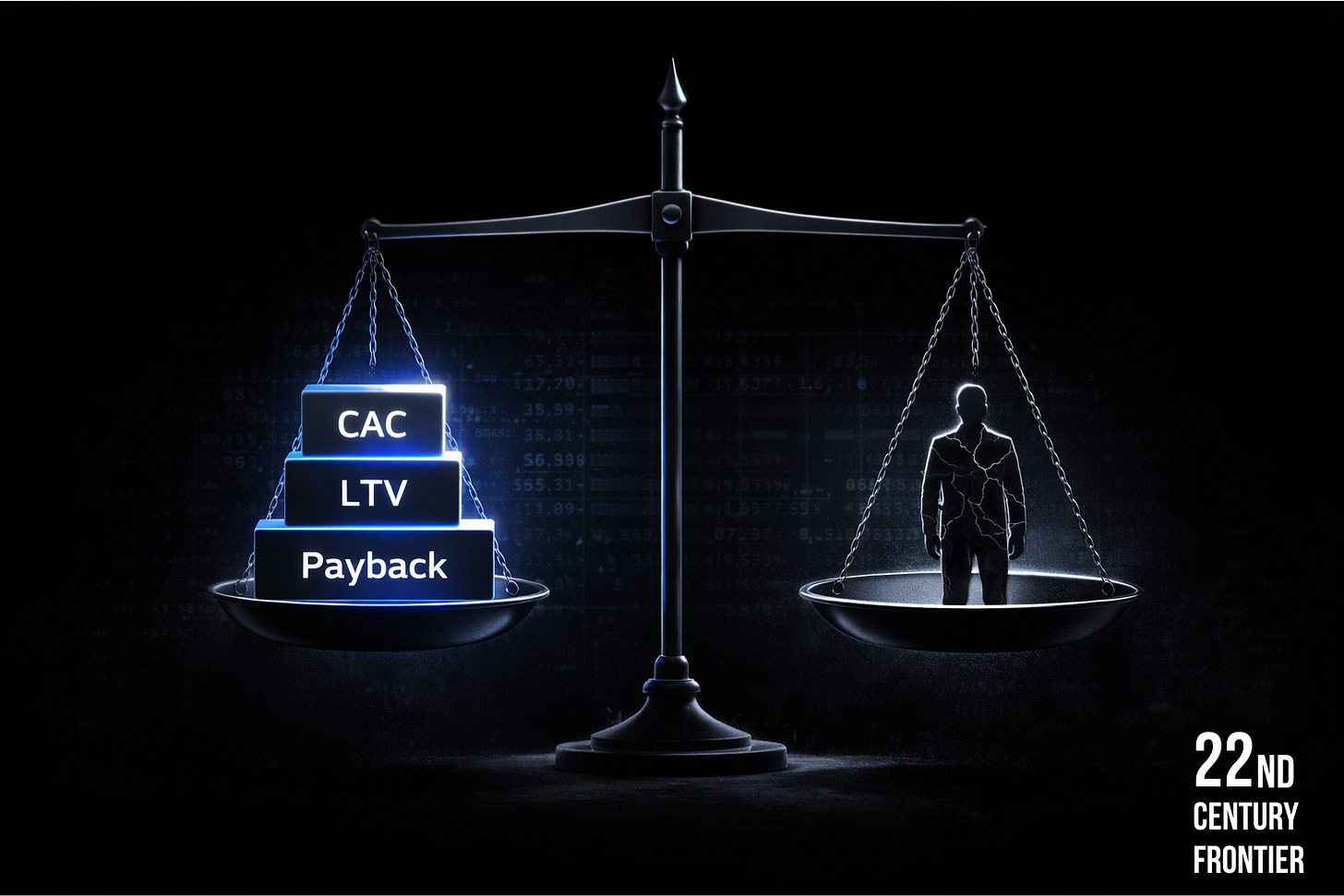

2. The Three Numbers That Matter

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

Lifetime Value (LTV)

Payback Time

3. Customer Acquisition Cost

CAC is the total cost to turn a stranger into a paying customer.

Early founders usually underestimate this number because they only count ads. That is a mistake.

There are two useful versions of CAC:

Surface-level CAC

This is what most people calculate.

Direct marketing spend divided by customers acquired.

Real CAC

This includes everything tied to acquisition:

Marketing salaries

Sales commissions

Agencies and contractors

Marketing software

Event costs

Content production

and more

If someone exists primarily to acquire customers, their cost belongs in CAC.

The rule here is simple:

Round Up, Not Down.

Optimism feels good but it kills companies.

4. Why CAC Almost Always Rises

Many founders believe CAC will fall as they scale.

In reality, the opposite is more common.

Early traction comes from:

High-intent early adopters

Underpriced channels

Founder hustle

Personal networks

Those do not scale forever.

As volume increases, you exhaust the obvious channels and move into colder audiences.

Conversion rates fall.

Competition increases.

CAC rises.

This is normal.

The mistake is building a business that only works at your cheapest acquisition layer.

5. Lifetime Value (LTV)

LTV answers a brutally simple question:

How much revenue does a customer generate before they leave?

You do not need perfect precision early. You need a conservative estimate that does not rely on hope.

LTV depends on:

Pricing

Retention

Expansion revenue

Purchase frequency

For subscriptions, a rough early proxy is monthly revenue multiplied by average customer lifespan.

For transactional businesses, it is repeat purchase behavior, not the first sale, that matters.

Big LTV buys you strategic flexibility.

It allows:

Higher CAC tolerance

Slower sales cycles

More experimentation

Small LTV forces discipline.

If customers do not stay long or spend much, acquisition must be cheap and fast.

Example: B2B workflow SaaS

Imagine a compliance automation tool sold to mid-sized logistics firms.

Monthly price: $120

Conservative retention: 14 months

LTV: ~$1,680

That number sets the ceiling for CAC.

If acquisition costs $1,200, the business might still work.

If it costs $2,000, the math collapses.

According to OpenView Partners, top-performing SaaS companies typically maintain an LTV to CAC ratio above 3:1.

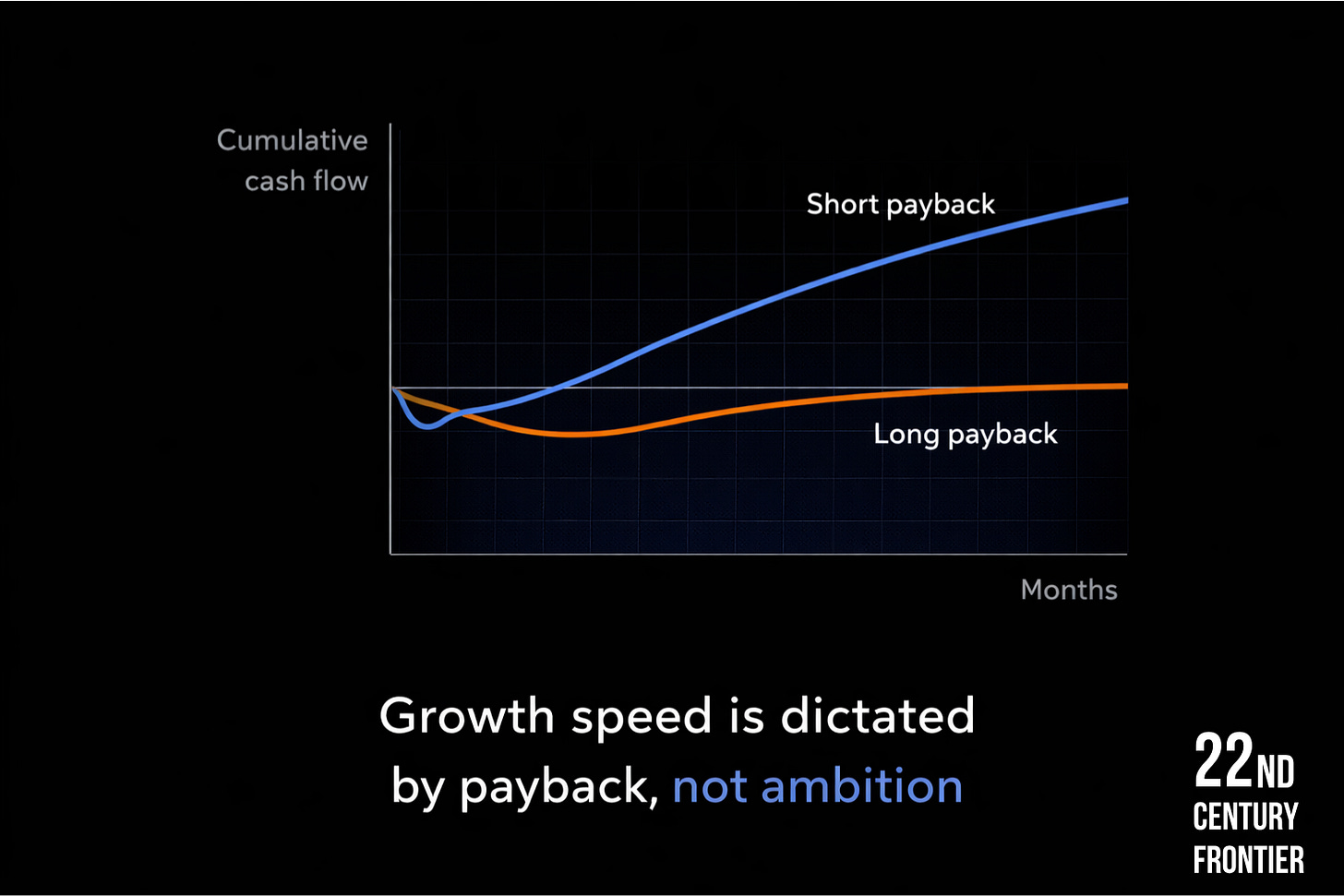

6. Payback Time

Payback time is where theory meets cash flow.

It answers this question:

How long does it take to earn back the cost of acquiring a customer?

This matters because growth consumes cash before it produces it.

A business with a 2-month payback can reinvest quickly and grow without constant fundraising.

A business with a 24-month payback must raise capital or slow down.

Neither is inherently wrong.

But confusing the two is fatal.

A simple illustration

Scenario A: Short payback

CAC: $90

Net monthly revenue per customer: $45

Payback: 2 months

Every customer funds the next one quickly. Growth compounds naturally.

Scenario B: Long payback

CAC: $720

Net monthly revenue per customer: $60

Payback: 12 months

Growth is possible, but only with external capital or extreme patience.

This is why two companies with identical LTVs can have radically different outcomes.

7. What Good Payback Numbers Actually Look Like

There is no universal benchmark, but patterns exist.

Early-stage, bootstrapped

CAC: under $100

Payback: under 3 months

LTV: conservative and proven quickly

SaaS

CAC: can be higher

Payback: under 12 months is generally acceptable

LTV: clearly expandable via retention or upsell

Ecommerce

First-order profitability is ideal

LTV must justify paid acquisition

Retention matters more than branding

8. The Trap of Believing Your Own Spreadsheet

Your early numbers will be wrong.

That is unavoidable.

What matters is not precision but direction.

Common early mistakes:

Assuming low churn without evidence

Ignoring support and infrastructure costs

Treating founder labor as free forever

Scaling before validating payback

Metrics are tools, not truth.

Use them to test reality, not to defend optimism.

9. The Three Phases Where Numbers Mature

Every scalable business passes through three stages:

Discovering real customer demand

Proving a repeatable economic model

Scaling what already works

True confidence in CAC and LTV only appears at the end of phase two.

Before that, you are making educated bets.

The mistake is scaling during phase one.

10. A Practical Way To Think Before Starting

When evaluating a new idea, ask:

Can I reach a specific audience cheaply?

Do they have a reason to keep paying?

Will cash return fast enough to fund growth?

If you cannot answer those, do not build yet.

Test acquisition.

Test pricing.

Sell manually.

Learn before committing capital.

Ideas are abundant.

Working unit economics are rare.

11. Final thought

Startups do not fail dramatically.

They fail quietly, one bad customer cohort at a time.

CAC, LTV, and Payback Time are not exciting.

They will not get you invited on podcasts.

But they decide everything that happens after the launch post fades.

Ignore them and you build a story.

Respect them and you build a business.

Everything else is noise.

Continue Exploring the Frontier

If this piece resonated, you may want to go deeper.

Here are three recent articles readers found especially useful:

Each one tackles a different part of the same challenge: building with intent, not hope.

If you are serious about shaping the future rather than reacting to it, you are exactly where you should be.

Omg, yes! If your business numbers do not make sense on the spreadsheet (and I'm talking real numbers like CAC, as you've mentioned, and not future financial projections based on optimistic assumptions), then it would be difficult to grow sustainably.

Sure, ambition, storytelling, publicity, differentiation, and a good team matter for success, but financial health is what is ultimately going to keep it in business.

Me simplifying business "create customers, keep customers" 👈 This is the job 🎯