Choosing a Cofounder: The Hard Questions Most Founders Skip (But Shouldn't) 🎯

The conversations that prevent future disasters

Choosing a cofounder is not networking. It is not brainstorming. It is not vibes.

It is structural.

A startup is a long stress test disguised as a company.

Deadlines slip.

Money runs out.

Investors say no.

Customers churn.

Plans collapse.

Under pressure, personalities amplify.

Small differences in expectations become major fractures.

Most founder breakups do not happen because someone is incompetent.

They happen because assumptions were never discussed.

The smartest founders do not look for chemistry first.

They look for clarity.

Below is a structured set of questions that reveal whether someone is a true partner or just a temporary collaborator.

Sponsor Highlight: EuphoriaTech Group ✨

Where founders, executives, and top creators connect

EuphoriaTech Academy is a community-first membership giving you access to Influencer Syndicate Communities and a Founder & Executive Network.

Collaborate, share insights, and build real opportunities with people actively shaping tech and business.

Key Takeaways

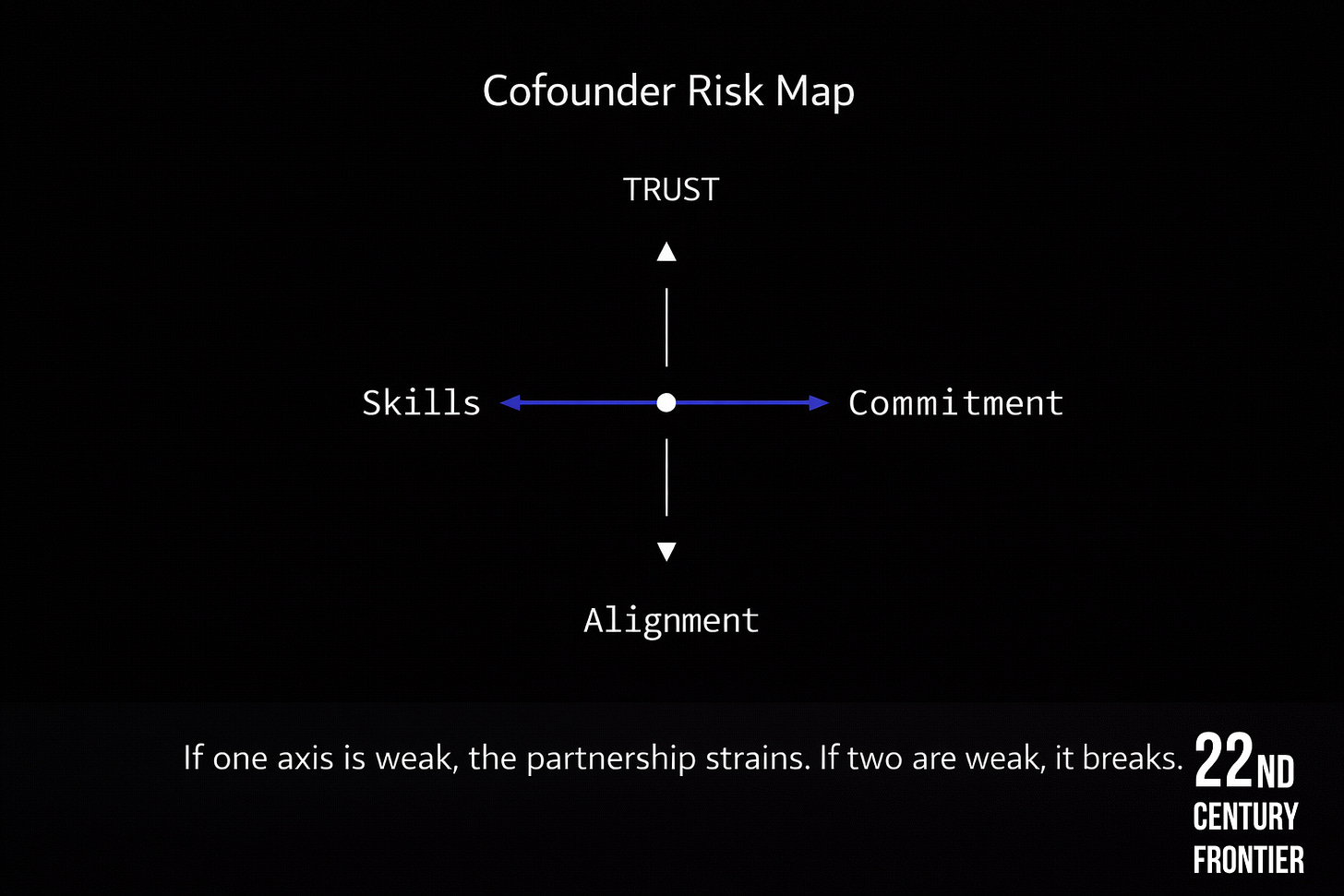

The most important startup decision is not the idea. It is who you build with when things stop going smoothly.

Strong founding teams are defined by complementary strengths, not shared enthusiasm or similar backgrounds.

Misalignment on risk, time commitment, or definition of success causes more founder breakups than bad markets.

Conflict is inevitable. What determines survival is how founders handle disagreement, pressure, and trade-offs.

The safest way to choose a co-founder is not conversation. It is testing collaboration in real work before committing.

Table of Contents

Capability and Role Clarity

Motivation and Risk Tolerance

Commitment and Availability

Decision Making and Power

Values Under Pressure

Conflict Style and Self-Awareness

Equity, Fairness, and Expectations

Vision and Definition of Success

Testing Before Committing

Final Thoughts

1. Capability and Role Clarity

Before chemistry, you need competence.

Not vibes.

Not potential.

Actual, demonstrated ability.

Key questions to explore:

What have you built, shipped, sold, or led end to end?

What work do you consistently perform better than most people you know?

What work do you avoid or procrastinate on?

Strong founding teams are complementary, not redundant.

Two people who both want to “set vision” but avoid execution create paralysis.

Two people who both want to build but avoid selling create obscurity.

A useful test is simple:

If the company succeeds, can you clearly explain why each of you was essential?

If the answer feels vague, you are early.

2. Motivation and Risk Tolerance

People start companies for different reasons. None are inherently wrong. Misalignment is.

Some are driven by independence.

Some by financial upside.

Some by craftsmanship.

Some by status.

Some by curiosity.

The danger is assuming you share the same reason.

Ask questions that force trade-offs:

What would make this feel like a failure to you?

How much financial risk are you willing to absorb personally?

If this takes five years instead of two, are you still in?

If growth is slower but more sustainable, is that acceptable?

A founder who needs early validation will behave very differently from one who can tolerate long periods of ambiguity.

Under stress, those differences widen.

3. Commitment and Availability

Many partnerships break not from conflict, but from asymmetry.

One person is all in.

The other is half in.

Resentment follows.

Clarity matters more than ambition.

Discuss explicitly:

Are we both full time? If not, when does that change?

How many months of personal runway do you realistically have?

What happens if we cannot pay ourselves for a period?

Are there constraints that would force you to step back unexpectedly?

This is not about judgment.

It is about predictability.

Unspoken constraints become future emergencies.

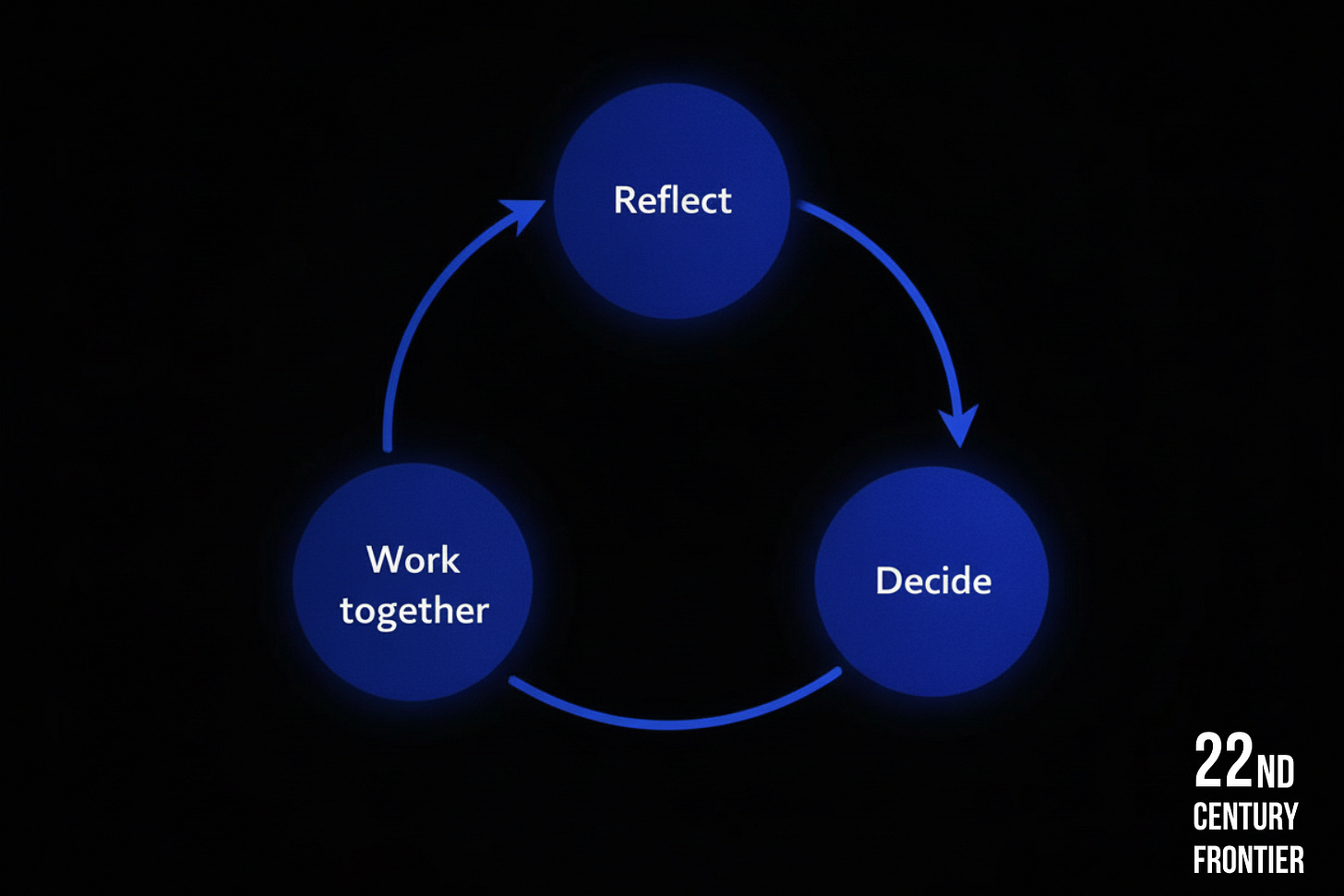

4. Decision Making and Power

Most founder conflict surfaces when a decision must be made quickly and stakes are high.

Avoiding this conversation does not prevent conflict.

It guarantees it.

Important areas to clarify early:

Who is responsible for final decisions?

When do we debate versus defer?

What decisions require mutual agreement?

How do we resolve deadlock?

Even highly collaborative teams benefit from a clear decision owner.

Speed matters more than consensus in early companies.

If both of you expect veto power everywhere, you are building friction into the system.

5. Values Under Pressure

Values only matter when they cost something.

Anyone can agree on integrity and respect in the abstract.

What matters is behavior when incentives clash.

Explore scenarios:

How do you feel about cutting corners to survive?

How do you treat people who underperform?

What happens when an employee is also a friend?

How transparent should we be with bad news?

Listen less to the stated answer and more to the reasoning.

People reveal themselves in how they justify trade-offs.

6. Conflict Style and Self-Awareness

Conflict is not a sign of a bad partnership.

Avoidance is.

The question is not whether you will disagree.

It is how disagreement is handled.

Useful questions:

How do you typically react when challenged?

What feedback do people give you repeatedly?

What stresses you out the most in work settings?

How do you cool down after conflict?

Pay attention to defensiveness.

A founder who cannot acknowledge weakness early will struggle to grow later.

A powerful question to ask is:

What would someone who dislikes working with you say about you?

The willingness to answer honestly is itself a signal.

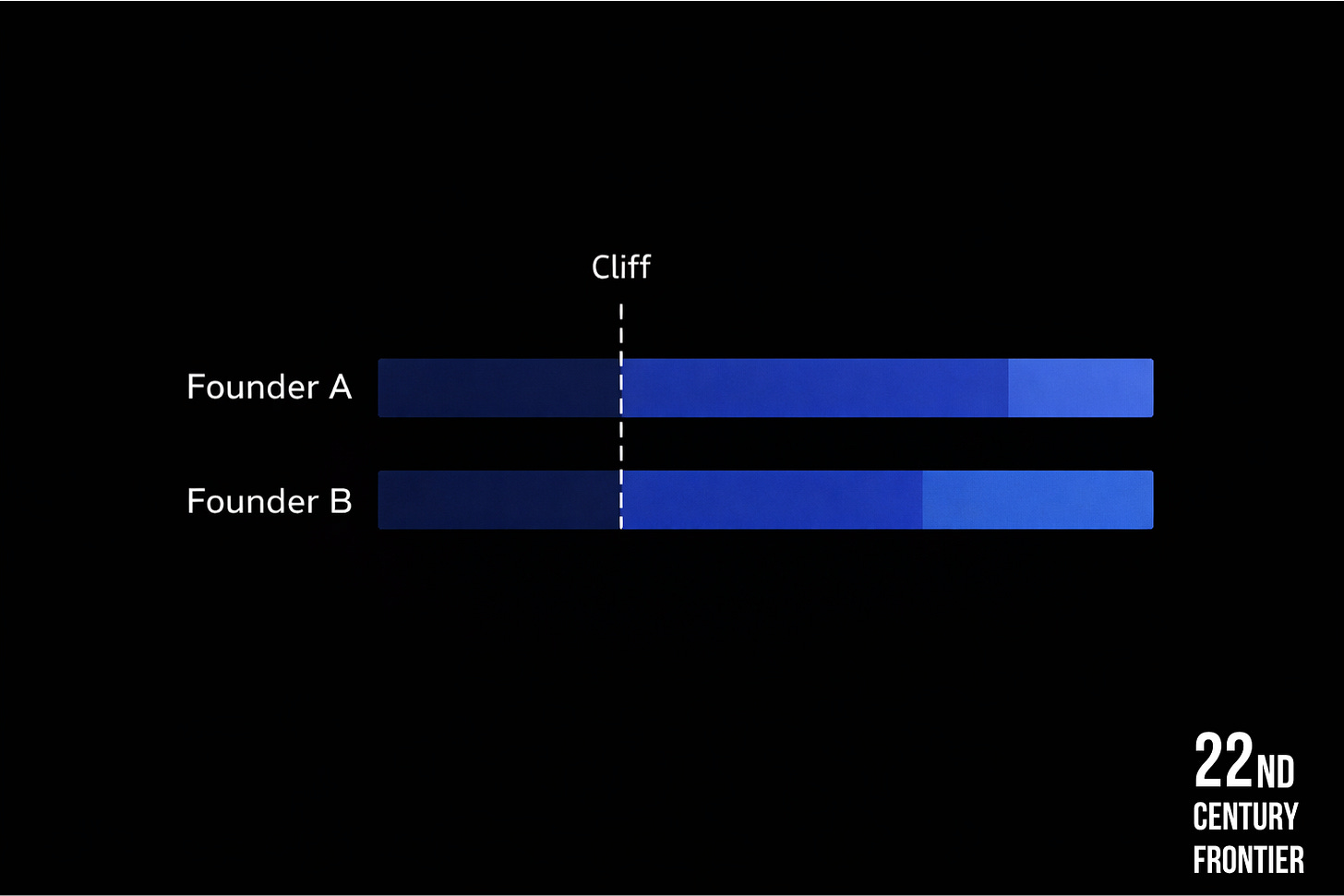

7. Equity, Fairness, and Expectations

Equity discussions are uncomfortable.

That is exactly why they should happen early.

Avoid vague promises.

Replace them with explicit terms.

Clarify:

How do we think about ownership and contribution?

What happens if one of us leaves early?

Are we open to vesting and cliffs?

How do we treat unequal time or capital contributions?

Fair does not always mean equal.

But unclear always means dangerous.

Documenting this early protects the relationship later.

8. Vision and Definition of Success

Two people can want to build a company and still want very different outcomes.

Misalignment here often surfaces years too late.

Discuss:

What does success look like personally?

Are you aiming for maximum scale or meaningful independence?

How do you feel about acquisition versus long-term operation?

At what point would you want to exit?

The goal is not identical answers.

The goal is compatible ones.

9. Testing Before Committing

Words are cheap.

Behavior is data.

Before formalizing anything, work together in a real context.

Options include:

A short consulting project

A paid pilot with a customer

Building a small product together

Selling something manually

Time-bound collaboration reveals far more than interviews ever will.

If working together for 30 days feels heavy, scaling that relationship will not fix it.

10. Final Thoughts

Choosing a co-founder is one of the highest-leverage decisions you will ever make.

It is not about finding someone impressive.

It is about finding someone compatible under pressure.

Ask questions that surface reality, not aspiration.

Favor clarity over comfort.

Test before committing.

The best founding relationships are not perfect.

They are explicit.

And explicit beats optimistic every time.

Continue Exploring the Frontier

If this piece resonated, you may want to go deeper.

Here are three recent articles readers found especially useful:

Each one tackles a different part of the same challenge: building with intent, not hope.

If you are serious about shaping the future rather than reacting to it, you are exactly where you should be.

Biggest wealth creators or dilutors - life partner and Business partner(s). Choose wisely 🤔

All the points you touched on are truly powerful and important. Thank you for sharing your work, Petar. In addition to those factors you beautifully compiled and Chris Tottman’s comment below may I add one thought? It’s a long journey. Only time will show who you and your co-founder will become along the way. You may know yourselves today, but you don’t yet know how you’ll respond to real success, real failure, or major outcomes whether that’s becoming billionaires, going through an exit, or an IPO.

And things inevitably shift when more powerful actors enter the stage such as investors, growth executives, and others. Collaboration evolves as the circle grows. Just my two cents.